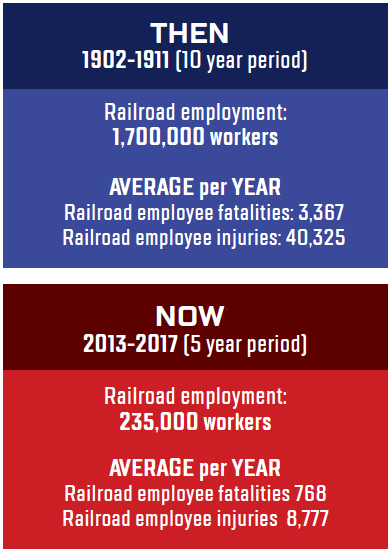

A hundred years ago, the accident rate among railroad workers was horrendous. As many as 40,000 railroad employees were injured every year, many crippled for life, and nearly 4,000 workers annually lost their lives in accidents. Next to coal mining, railroading was the most dangerous kind of work.

Railroads in the early 20th century were the predominant form of transportation for people, freight, parcels, livestock and the U.S. mails. The United States had the densest network of rail lines in the world – 217,000 miles of track. In 1916, there were 185 Class I (multi-state) railroads, compared to only seven today. There were 1600 smaller railroads, against 531 today.

Back then, speed was more important than safety. Many of the bigger railroads were locked in fierce competition with each other. They ran multiple trains on single tracks. There was no radio communication between trains and dispatcher; railway signaling devices were still evolving. Control of trains depended on time-tables and train orders — telegraphed instructions from dispatchers which were picked up by train crews as they passed a station.

The orders specified the meeting point for trains and which train had to move into a passing track to let the other train go by. Sometimes an “extra” train, not on the timetable, was slipped in during heavy traffic periods.

With such high-volume traffic operating on congested tracks, a misdirected train order, mechanical breakdown, or simple human error could cause disaster – as witness this spectacular smash-up that occurred on the Rock Island Line near Grundy Center, Iowa, on June 17th, 1913:

An “extra” train carrying hogs and cows from Iowa Falls was running an hour behind the regular scheduled stock train. It made two stops to pick up more animals, which reduced the separation time between the two trains. About noon, the “extra” train neared the railyard at Grundy and stopped to take on water for the engine and the animals. The engineer did not pull his train fully into the siding, so the caboose was left standing out on the mainline. The train’s conductor didn’t think to put a flag man by the caboose to warn approaching trains. He probably misjudged the time before the scheduled train would appear.

Meanwhile, the regular train, with 30 cars of hogs and cattle, had caught up with the “extra”. As it rounded a curve “at a good clip,” the engineer on board saw the caboose ahead. All he could do was hit the brakes and throw the engine in reverse; then he and the fireman jumped for their lives.

With a tremendous crash, the regular train locomotive slammed into the wooden caboose, sending it 20 feet into the air in a shower of splinters and twisted steel. No one was in the caboose. The locomotive then derailed and plowed 30 feet through the dirt before tipping over. The coal tender behind it jack-knifed across the track.

With a tremendous crash, the regular train locomotive slammed into the wooden caboose, sending it 20 feet into the air in a shower of splinters and twisted steel. No one was in the caboose. The locomotive then derailed and plowed 30 feet through the dirt before tipping over. The coal tender behind it jack-knifed across the track.

A hog car behind the tender was thrown off the rails, spilling its cargo of squealing pigs into a ditch. A cattle car immediately behind the hog car then slammed into the over-turned locomotive. Escaping steam from the ruptured boiler scalded the frantic cows trying to get away; some of the cows had to be shot to put them out of their misery. By a miracle no rail worker was hurt or killed.

A wrecking crew turned up at 5 P.M. and began clearing the wreckage, while hundreds of townfolk stood watching. Railroad traffic was held up for 12 hours before the line was opened. The engineer of the regular train was blamed for approaching the Grundy yards at too great a speed, and the conductor of the extra train was blamed for not putting out a flagger.

This article is reprinted from the Summer 2018 edition of The Aldon Express, a regular publication of Aldon Company, a maker of rail safety and track repair products since 1904.

Print this page